Tuesday, June 21, 2005

An installment of the Star Trek 60s follows. For the essay on H.G. Wells and Gene Roddenberry, click here.

Next Week: More Wells and War of the Worlds.

by William S. Kowinski

This summer, TCM is showing some of the classics of what it calls "Cold War Cinema" as part of its "Future Shock" science fiction series. At the same time, producers of the fall season's sci-fi are talking the same language: of sci-fi stories responding to a sense of threat, engendered this time by 9-11, terrorism and warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Former Star Trek producer Brannon Braga, now executive producer of the upcoming CBS drama "Threshold," which is about a classic 1950s Cold War Cinema theme---invasion and subversion from outer space--- last week acknowledged that his show reflects the fear of terrorism that "must be in the zeitgeist...There's something in the blood right now. There can be no doubt that, even subconsciously, 9/11 is a thematic undercurrent in our show, for sure."

In a Media Week story by A.J. Frutkin, several other producers and analysts were quoted on ABC's "Invasion" and NBC's "Fathom" as also reflecting these anxieties.

This fear and uncertainty is also reflected in the upcoming Steven Spielberg version of "War of the Worlds," opening in theatres in time for the Fourth of July weekend.

What's especially fascinating about this mood is its grip on the unconscious. When the danger is past and the movies responding to it are outdated, it's easy to dismiss them as reflecting Cold War "paranoia." In fact it largely was paranoia, just as today's fears are: out of proportion to cause, and ranging much wider in search of enemy threats than the actual sources of danger.

Besides expressing fears, these sci-fi stories demonstrate how fears get translated and displaced into fantastic situations, both to tame them a bit, but also to give them voice when expressing the wrong kind of doubts might invite general disapproval, even charges of disloyalty.

Much of Cold War Cinema represents what I call the science fiction of unconsciousness: it simply expresses in different terms the fear and anxieties that don't or can't get expressed on their own terms. Will these new shows simply exploit these fears in similar if updated examples of the sci-fi of unconsciousness? Or will they apply the sci-fi of consciousness to these issues, the way that classic Star Trek did?

To help you answer that question for yourself, perhaps the following discussion of some of the films in the TCM series, and Cold War Cinema in general, will shed some light on what to look for in the new shows this fall.

Text continues after illustrations

On the day of the first atomic bomb test in July 1945, no one knew what would happen. About half the scientists didn't think it would explode at all. Enrico Fermi was taking bets that it would burn off the earth's atmosphere.

It did explode, with such brightness that a woman blind from birth traveling in a car some distance away saw it. "A colony on Mars, had such a thing existed, could have seen the flash," writes Gerard J. DeGroot in his new book, '>The Bomb: A Life. "All living things within a mile were killed, including all insects."

The Bomb was more than the most powerful weapon in history, although the fact that it was, led to much that happened later that summer and in the years afterwards. Scientists like Leo Leo Szilard (motivated in part by what he remembered from the H.G. Wells novel that predicted-and named-the atom bomb in 1914) had urged the U.S. to develop the Bomb because they feared that Germany might build it first.

But Germany hadn't, and was now defeated. Japan's defeat was all but inevitable by the spring of 1945. So the day after the first test, Szilard sent government officials a petition signed by 69 project scientists arguing that to use the bomb would ignite a dangerous arms race and damage America's post-war moral position, especially its ability to bring "the unloosed forces of destruction under control."

But the momentum was all towards using the Bomb, not just demonstrating it. The second atomic bomb was already on its way to the Pacific, and General Leslie Groves, the senior military official in charge of the Bomb project, began making a case that Szilard was a security risk.

Some believe that the Bomb was dropped on Hiroshima as much to impress the Soviet Union as to defeat Japan. The arms race between the Soviets and U.S. dominated the next 40 years. In the U.S., to criticize the Bomb became unpatriotic, an act of disloyalty that only helped the Communist enemy. And so people were silent and compliant, and streamed into air-conditioned theatres to see movies that expressed the doubts and fears they were not allowed to articulate openly.

These movies expressed all kinds of suppressed and repressed emotions, including forbidden sex and hidden violence, so these films of varying quality could be lurid-and especially advertised as lurid-- in many different ways.

Many of these films also tapped into the feeling that with the Bomb, humanity had committed sacrilege, had transgressed by learning secrets of power that man was not meant to know.

But there are several different ways that various movies relate to the Bomb and the Cold War.

One kind of Cold War era movie is the space invasion film, a stand-in for the threat of attack from the sky by earth aliens (i.e. Soviets.) Whatever actual threat existed, it was government policy to encourage the idea. "In order to make the country bear the burden, " said President Eisenhower's Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, referring to the arms race of the Cold War, "we have to create an emotional atmosphere akin to a wartime psychology. We must create the idea of a threat from without."

The "bolt from the blue" was burned deep in the modern American psyche by the devastating surprise air attack on Pearl Harbor. (Hiroshima, some observers felt, was in part a revenge for that attack.) But even before that attack occurred, Americans were nervous about one, as proven by the panic during the '>Orson Welles radio broadcast of H.G. Wells' "The War of the Worlds" in 1938, three years before Pearl Harbor.

So it shouldn't be surprising that one of the first and probably the best Cold War era space invasion film was the 1953 George Pal production of "'>War of the Worlds." Since it isn't included in this series---and since I'll be writing about it next week, prior to the Spielberg version's general release-I'll say only that it was the best film of that era in expressing fears of a technologically superior enemy with intelligence so alien and hostile that communication with it was impossible.

The analogies to the Soviet had to do with their surprising technical achievements---they exploded their own atomic bomb and hydrogen bomb far sooner than Americans predicted. American scientists as well as citizens would be shocked again a few years later when the Soviets orbited the first artificial satellite, and rocketed the first man into space.

Add to that the image of the Soviets as incomprehensibly alien. This was partly a product of the Soviets' closed society (few American journalists or visitors permitted inside Russia), partly due to Communism, which was portrayed as an alien system: economic, political, cultural and even in terms of basic beliefs, for the fact that the Soviet Union was officially atheist was often stressed in American descriptions.

It was also partly because of self-serving western propaganda and the dramatic effect of portraying Russians as threatening and even superhuman---when they weren't been portrayed as backward dolts driving broken-down old cars without tail fins. Demonizing the enemy is an old habit that nation states found helpful in galvanizing war efforts, including the U.S. when it mocked and demonized the Germans and Japanese racially. The stupidity if not cynicism of this ploy becomes obvious when enemy nations become our friends, as these did, and as Russia now is.

The theme of invasion by aliens is represented in the TCM festival by several films illustrating different aspects of the genre. "'>Earth vs. the Flying Saucers"(1956) is a pure invasion drama that also takes advantage of the popular phenomenon of UFO sightings, which became prominent as the Cold War began. It features B movie plot and acting but A level visual effects by the master of stop-motion, Ray Harryhausen.

It takes place in Washington, D.C., as did the earlier "'>Day the Earth Stood Still" (1951), but except for the location, the trigger-happy soldiers and the fact they're both in black and white, this one has nothing in common with the Robert Wise masterpiece, which unmasked the self-destructive madness of the Cold War just as it was starting. The weapon the earthlings eventually employ is a nice metaphor for the brassy 50s, but its amusement quotient is dimmed by recent news that far more sophisticated sonic weapons are actually being deployed in the Middle East.

Another alien invasion film showcasing the talents of Ray Harryhausen is "'>20 Million Miles to Earth" (1957), with a creature reminiscent of "King Kong" in its basically sympathetic nature, goaded into destructive behavior. Not a memorable film, it suggests a slightly different attitude towards the Cold War.

The dogma of Marxist Communism was that it would be an international revolution of the proletariat (workers), so Americans were told (most often by FBI Director J.Edgar Hoover) to be on guard against Communists organizing inside the country and promoting Communist ideas to the unwary. So Communist subversion as well as invasion was to be feared and opposed. The threat of subversion led to numerous excesses and mendacities, like McCarthyism and blacklisting---and to another genre of Cold War cinema.

A 1950s classic straddles the line between invasion and subversion themes is '>"The Thing" (1951), originally called "The Thing From Another World." Because the creature is already here, buried in the Arctic ice and set free by human's digging it up, it has elements of the subversion theme. But this taut drama directed by Howard Hawks with his trademark fast-paced but low-key dialogue also provided the key phrase of the space invasion films: "Watch the Skies!"

'>"The Blob" (1958) was a hybrid of its time: part space invasion, part vampire movie, creature movie, and mostly teenagers versus the system movie, it is remembered mostly for introducing Steve McQueen. Some sci-fi aficionados like this one; I didn't. Maybe it was the silliness of the song.

Steven Spielberg's "'>Close Encounters of the Third Kind" is included in the TCM festival, and can be seen in this context as the antithesis to "Earth vs. the Flying Saucer" and its ilk. It's not just a matter of the aliens being good rather than evil, or even that humans invite them rather than freak out and start shooting at their first appearance.

What's alien about the aliens in these movies is some exaggerated facet of human nature or behavior: often the bestial qualities. In this Spielberg movie, humanity can be seen as going to some lengths to welcome parts of human nature that got frozen out by Cold War psychology--like listening to intuitions and outside-the-mainstream ideas and feelings instead of fearing them, and a willingness to wonder rather than panic in the face of the unknown, all rewarded with a glimpse of the cosmic possibilities.

Finally, the space invasion genre reaches self-parody in "'>Mars Attacks"(1996), though it was based on a set of bubble gum cards from the 1960s. But by the 90s, the Russians were allies and there were clearly no aliens on Mars, so the space invaders were an occasion for social satire of varying effectiveness.Directed by Tim Burton, it stars Jack Nicholson and a host of current and past movie stars and camp icons.

"'>Village of the Damned" (1960) is about children as aliens with their subversive ideas, made at the start of the decade when the "juvenile delinquency" of the fifties became the youth rebellion. Civil Rights and anti-war protestors were sometimes said to be "controlled" by alien Communist influences, even taking marching orders from Moscow. This film is a mild preview, with a nice performance by George Sanders.

There were two more films on this theme (neither in this festival.) In "'>Children of the Damned" (1964), the American version, the children are mutants from the human future (which s/f experts will recognize from Olaf Stapledon's classic novel, Odd John). Some of the adults argue that the children are here to bring peace, but fear wins out and they are eradicated by the military.

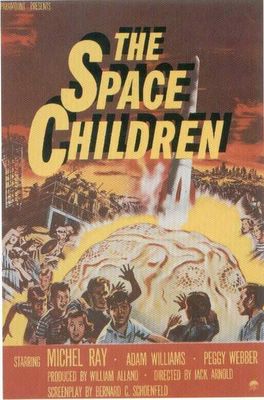

A more pointed film on this theme was The Space Children (1958) directed by Jack Arnold, famous for the Gill Man movies and other 50s sci fi classics. An alien intelligence taps the minds of the children of scientists to stop a nuclear bomb test. The parents freak out and attack them, but they manage to destroy the warheads by mind power. But the movie is more than this bare plot, revealing the crassness and cruelty of standard 1950s domesticity. It prefigures the 1960s generation gap and youth culture in a sci-fi setting.

There were two other Cold War Cinema themes not represented in the TCM lineup. One was the Atomic Apocalypse film: stories of civilization destroyed by nuclear war, and how the survivors cope, or don't. These included "The World, The Flesh and the Devil" (1959) and "'>Panic in the Year Zero" (1962) and were forerunners of the "post-apocalypse" films like the Mad Max series, as well as the more substantial films that dramatized effects of nuclear war, like the highly influential "'>On the Beach"(1959 ) or the lesser known but deeply affecting "'>Testament" (1983), and in one prominent case, exposed its absurdity with comedy: "'>Doctor Strangelove" (1964.)

The other probably spawned the most films, and represented perhaps the deepest and most unique fear of the nuclear age. The secrecy of the Bomb's development morphed easily into Cold War lies, particularly about the effects of radiation. From Hiroshima to the hydrogen bomb, and even after that through decades of nuclear tests, officials denied or minimized evident radiation damage to humans. The aforementioned General Groves even told a Congressional committee that death from radiation was "very pleasant."

Nevertheless, reports got out, some quite graphic, from tabloid exposes to serious journalism, like John Hersey's landmark '>Hiroshima. Information included eye-witness accounts not only of the sickness, suffering and death of those exposed to fallout, but of mutations to children born to parents affected by radiation. In a book published in 1954, Dr. David Bradley reported on 406 Pacific Islanders exposed to H-Bomb fallout: nine children were born retarded, ten more with other abnormalities, and three were stillborn, including one reported to be "not recognizable as human."

Such information, especially when government officials implied that talking about it was unpatriotic, went underground, direct to the national unconscious. The fears engendered by these new horrors could safely be expressed in the guise of what became known as the "bug-eyed monster" movies.

One of the best examples of the radiation monster genre was one of the first---'>Them!" (1954): Radiation from atomic testing in the New Mexico desert mutated a colony of ordinary ants into a race of giant ants, killing, breeding and preparing to swarm on Los Angeles and other cities, where they could begin their conquest of humanity. (This isn't in the TCM lineup.)

The film is notable today partly because it features so many future television drama stars: James Whitmore ("The Law and Mr. Jones"), James Arness ("'>Gunsmoke"), Fess Parker in a small part (Walt Disney saw him in this film and signed him up to play '>Davy Crockett, the first major baby boomer TV hero) and in an even smaller part, Leonard Nimoy.

But it is also among the most skillfully made of the bug-eyed monster films, and the clearest in its enunciation of the theme. The movie ended with this exchange: "If these monsters got started as a result of the first atomic bomb tests in 1945, what about all the others that have been exploded since then?" asks the Arness character, an FBI man. "I don't know," says the beautiful woman scientist. "Nobody knows," says the elder scientist, her father. "When man entered the atomic age, he opened the door into a new world. What we eventually find in that new world nobody can predict."

All kinds of mutations would follow: giant grasshoppers, preying mantises, crabs, etc. There were also human mutations---the best film of this variation was another one by Jack Arnold, "'>The Incredible Shrinking Man" (1957) from a novel by Richard Matheson (who Original Series Trek fans will recall as author of the "two-Kirks" episode, "The Enemy Within.")

It also includes what is likely the first environmental doomsday film, "'>Soylent Green," which was prophesizing global warming in 1972. The highlight is Edward G. Robinson's death scene, which preceded his actual death by a few weeks. The images he watches of a beautiful earth, the one that we still have at the moment, is even more moving now, as global heating has in fact begun.

Monday, June 20, 2005

1966 was a big year for Bob Dylan: electric music '>world tour, release of "'>Blonde on Blonde" and a motorcycle accident in July that led to his disappearance for several years.

historical and cultural context for Star Trek's first season

Oct1. Chinese Communists celebrate 17th anniversary of the establishment of their regime.

Oct. 4. The small African Kingdom of Lesotho, previously called Basutoland, gained independence from Great Britain, following the September 30 independence of the Republic of Botswana. Only two of the former British colonies in Africa remain. France, Portugal and Spain still have African colonies.

Oct.5: World Series begins, with Los Angeles Dodgers and their ace pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale the heavy favorites. However, the series is won by the Baltimore Orioles in four straight; the last three are shutouts.

Oct. 6: "'>The Enemy Within"

Oct. 7: President Johnson proposes increasing trade in non-strategic items with USSR and eastern bloc nations, and permission to U.S. citizens to travel to Communist countries which they had been forbidden to visit.

Oct. 13: "'>Mudd's Women"

Oct. 20: Congress passes legislation to finance the rebuilding of large urban areas.

Oct. 20: "'>What Are Little Girls Made Of?"

Oct. 24: Some 200 protestors were arrested in Grenada, Mississippi as they protested against harassment of black students at two recently integrated schools.

Women described as "housewives" staged supermarket boycotts to protest rising food prices in a number of communities in the U.S.

Oct. 26: President Johnson visits U.S. troops in South Vietnam. He flew secretly to the most secure base in country and stayed for 44 minutes.

The Beatles '>Revolver is the Billboard number one album. John Lennon is on location, acting in the film "'>How I Won the War;" Paul McCartney is writing music for the film, '>"The Family Way," and George Harrison is in India with '>Ravi Shankar.

New movies being reviewed: John Huston's"'>The Bible," "'>Georgy Girl, "'>Morgan!" starring David Warner and Vanessa Redgrave.

Oct. 27: "'>Miri"

For more detailed background on the Star Trek 60s, click here.