Star Trek: Alternative Futures has received an amazing response around the Internet. If you missed it or would like to check out new comments, click here.

This week: Connections between HG Wells and Star Trek. Coming: more on Wells' science fiction novels (and their film versions), and on the various versions of The War of the Worlds, before a consideration of Steven Spielberg and his version which opens late this month.

The expanded version of my essay on Wells and The War of the Worlds that appeared in the SF Chroncile can be found here.

Monday, June 13, 2005

Star Trek Roots: HG and GR

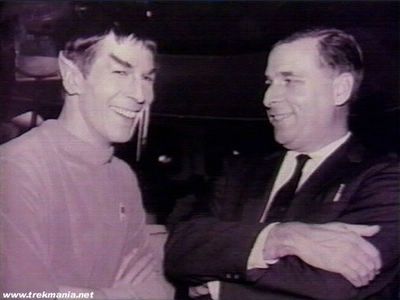

There are many intriguing connections and parallels between the lives, work and ideas of H.G. Wells and Gene Roddenberry. They were both born into relative poverty in constricted circumstances. Health problems in childhood turned them both to reading, and changed their lives. They both had a spotty mixture of scientific and literary education.

They were both self-taught professional writers, and gravitated towards the most popular storytelling medium of their time. They used pretty much the same method and philosophy of science fiction storytelling. They both became the best-known storytellers about the future of their era, and they both revolutionized how science fiction stories would be told after them. They both championed the science fiction of consciousness. Along the way they both became celebrated figures, influential in the larger world.

(Wells was referred to by friends as "HG," and Roddenberry was and still is often called "GR." For convenience, I'll employ these initials much of the time.)

H.G. Wells wrote his first science fiction some 70 years before Star Trek (which is the amount of time that separates Kirk's Enterprise from Picard's in the Star Trek universe.) It's possible to draw a straight, solid line between HG's approach to science fiction and GR's approach to Star Trek. That line would run through at least one important if obscure figure who wrote in the period about halfway between them, and more recently it would widen to include the ABCs of GR's generation (Asimov, Bradbury and Clarke.) Anyway that's the argument I'm about to make in the course of this brief look at some of what connects HG and GR.

text continues after illustrations

There are many intriguing connections and parallels between the lives, work and ideas of H.G. Wells and Gene Roddenberry. They were both born into relative poverty in constricted circumstances. Health problems in childhood turned them both to reading, and changed their lives. They both had a spotty mixture of scientific and literary education.

They were both self-taught professional writers, and gravitated towards the most popular storytelling medium of their time. They used pretty much the same method and philosophy of science fiction storytelling. They both became the best-known storytellers about the future of their era, and they both revolutionized how science fiction stories would be told after them. They both championed the science fiction of consciousness. Along the way they both became celebrated figures, influential in the larger world.

(Wells was referred to by friends as "HG," and Roddenberry was and still is often called "GR." For convenience, I'll employ these initials much of the time.)

H.G. Wells wrote his first science fiction some 70 years before Star Trek (which is the amount of time that separates Kirk's Enterprise from Picard's in the Star Trek universe.) It's possible to draw a straight, solid line between HG's approach to science fiction and GR's approach to Star Trek. That line would run through at least one important if obscure figure who wrote in the period about halfway between them, and more recently it would widen to include the ABCs of GR's generation (Asimov, Bradbury and Clarke.) Anyway that's the argument I'm about to make in the course of this brief look at some of what connects HG and GR.

text continues after illustrations

"Modern science fiction begins with H.G. Wells," writes Ursula Le Guin, the only science fiction author whose novels are assigned more often in schools than several by Wells.

Mary Shelley, Jules Verne and others are also often credited as starting science fiction, but Wells is certainly in the running. "With Wells, science fiction makes its debut, a new horizon for the imagination," writes Italo Calvino (who flirts with the form in several delightful books, including '>cosmicomics.)

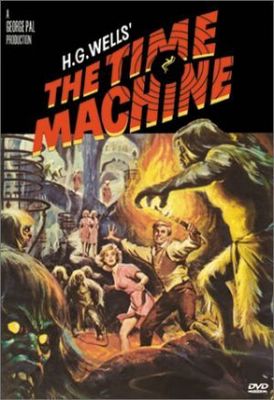

Wells wrote science fiction before the term existed (he called these novels and stories "scientific romances.") He wrote five of the most important and best known science fiction novels of all time: '>The Time Machine, '>The Island of Dr. Moreau, '>The Invisible Man, '>The War of the Worlds and '>The First Men in the Moon. He wrote hundreds of science fiction stories. Scholar Frank McConnell notes that of the fourteen basic themes of science fiction listed by James Gunn in his history of the form, "All but two major themes include a citation from a work of Well's and that usually the earliest. (The omission of Wells from those two is debatable.)"

A glance at the appendix to '>ALTERNATE WORLDS: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction, confirms this. Gunn lists a Wells story or novel as the first illustration of the themes of WAR, CATACLYSM, MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT, SUPERPOWERS, SUPERMAN, MAN AND ALIENS, MAN AND RELIGION, and MISCELLANOUS. Wells furnishes the 3rd, 4th and 5th instances out of 7 of the WONDERS OF SCIENCE theme, the second of PROGRESS and MAN AND SOCIETY, and the fourth of FAR TRAVELING. He is omitted from "MAN AND THE FUTURE (similar to Progress except that the purpose which shines through is descriptive rather than satirical)" and "MAN AND THE MACHINE similar to The Wonders of Science but in this case the emphasis is upon the relationship between man and his creation." It wouldn't be difficult to make a case for Wells being included in both of these.

If this is not remarkable enough, consider that Wells wrote all of the above-mentioned novels and most of the stories in just five years--- the last half-decade of the nineteenth century. He went on to write another 150 books, and while some of these are utopian and anti-utopian novels, and many are books about the future, HG seldom returned to the science fiction form. In 1933 he published an autobiography of more than 700 pages that barely mentions these novels that have since become his most enduring, and some are not named at all.

"But whatever his later development," scholar Frank McConnell writes, "it is undeniably the case that for those years of the 1890s...he was the sole and powerful creator of a new mode of storytelling: a mode that has increasingly, in all its complexity and in all its crudity, become the distinctive mythology of our time."

Mary Shelley, Jules Verne and others are also often credited as starting science fiction, but Wells is certainly in the running. "With Wells, science fiction makes its debut, a new horizon for the imagination," writes Italo Calvino (who flirts with the form in several delightful books, including '>cosmicomics.)

Wells wrote science fiction before the term existed (he called these novels and stories "scientific romances.") He wrote five of the most important and best known science fiction novels of all time: '>The Time Machine, '>The Island of Dr. Moreau, '>The Invisible Man, '>The War of the Worlds and '>The First Men in the Moon. He wrote hundreds of science fiction stories. Scholar Frank McConnell notes that of the fourteen basic themes of science fiction listed by James Gunn in his history of the form, "All but two major themes include a citation from a work of Well's and that usually the earliest. (The omission of Wells from those two is debatable.)"

A glance at the appendix to '>ALTERNATE WORLDS: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction, confirms this. Gunn lists a Wells story or novel as the first illustration of the themes of WAR, CATACLYSM, MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT, SUPERPOWERS, SUPERMAN, MAN AND ALIENS, MAN AND RELIGION, and MISCELLANOUS. Wells furnishes the 3rd, 4th and 5th instances out of 7 of the WONDERS OF SCIENCE theme, the second of PROGRESS and MAN AND SOCIETY, and the fourth of FAR TRAVELING. He is omitted from "MAN AND THE FUTURE (similar to Progress except that the purpose which shines through is descriptive rather than satirical)" and "MAN AND THE MACHINE similar to The Wonders of Science but in this case the emphasis is upon the relationship between man and his creation." It wouldn't be difficult to make a case for Wells being included in both of these.

If this is not remarkable enough, consider that Wells wrote all of the above-mentioned novels and most of the stories in just five years--- the last half-decade of the nineteenth century. He went on to write another 150 books, and while some of these are utopian and anti-utopian novels, and many are books about the future, HG seldom returned to the science fiction form. In 1933 he published an autobiography of more than 700 pages that barely mentions these novels that have since become his most enduring, and some are not named at all.

"But whatever his later development," scholar Frank McConnell writes, "it is undeniably the case that for those years of the 1890s...he was the sole and powerful creator of a new mode of storytelling: a mode that has increasingly, in all its complexity and in all its crudity, become the distinctive mythology of our time."

Today Wells is himself almost mythical. The first feature film version of '>The Time Machine and especially Nicholas Meyer's movie, '>Time After Time (in which Wells, played by Malcolm MacDowell, invents and uses an actual time machine) suggest that H.G. Wells was a Victorian gentleman, living in a spacious, lavishly furnished house, with at least one servant. But the author of The Time Machine actually lived in crowded rented rooms, and finished that book by writing at night with his head hanging out of an open window to escape the stifling heat of his apartment, while his landlady was complaining loudly about him below.

Eventually he did live pretty luxuriously. H.G. Wells was an important world figure for most of the first half of the twentieth century. His friends included Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin, Winston Churchill and William James, Bertrand Russell and Margaret Sanger. He lunched with Franklin Roosevelt, spent stimulating afternoons with Freud and evenings with Jung, talked privately in the White House with President Teddy Roosevelt, and in the Kremlin with Lenin and Stalin.

When President Woodrow Wilson asked the U.S. Congress to declare war on Germany and its allies in World War I, he did so with words taken from Wells: "the war to end all wars." As Wells struggled through his final illnesses and despair during World War II, he roused his energies to campaign for a postwar declaration of human rights. His efforts, ideas and his words contributed to the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights, officially adopted two years after Wells' death. In between, he wrote one of the best-selling non-fiction books of all time, '>The Outline of History.

"The minds of all of us, and therefore the physical world, would be perceptibly different if Wells never existed," George Orwell wrote. Upon Wells' death in 1946, the New York Times called him "the greatest public teacher of his time."

But it all came very close to not happening. The son of servants in a provincial town outside London, he was lower middle class-a precarious step removed from the industrial working class of the time. His mother meant for him to follow his brothers into trade as a draper's assistant, which was as high as anyone of their circumstances would normally aspire. Failure could be disastrous.

But a boyhood accident that kept him in bed began a lifelong passion for reading and learning. The books he was given during his convalescence---particularly the illustrated natural histories and stories of explorers-changed his life. "I am alive today and writing this autobiography," he wrote in1934, "instead of being a worn-out, dismissed and already dead shop assistant, because my leg was broken."

Eventually he did live pretty luxuriously. H.G. Wells was an important world figure for most of the first half of the twentieth century. His friends included Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin, Winston Churchill and William James, Bertrand Russell and Margaret Sanger. He lunched with Franklin Roosevelt, spent stimulating afternoons with Freud and evenings with Jung, talked privately in the White House with President Teddy Roosevelt, and in the Kremlin with Lenin and Stalin.

When President Woodrow Wilson asked the U.S. Congress to declare war on Germany and its allies in World War I, he did so with words taken from Wells: "the war to end all wars." As Wells struggled through his final illnesses and despair during World War II, he roused his energies to campaign for a postwar declaration of human rights. His efforts, ideas and his words contributed to the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights, officially adopted two years after Wells' death. In between, he wrote one of the best-selling non-fiction books of all time, '>The Outline of History.

"The minds of all of us, and therefore the physical world, would be perceptibly different if Wells never existed," George Orwell wrote. Upon Wells' death in 1946, the New York Times called him "the greatest public teacher of his time."

But it all came very close to not happening. The son of servants in a provincial town outside London, he was lower middle class-a precarious step removed from the industrial working class of the time. His mother meant for him to follow his brothers into trade as a draper's assistant, which was as high as anyone of their circumstances would normally aspire. Failure could be disastrous.

But a boyhood accident that kept him in bed began a lifelong passion for reading and learning. The books he was given during his convalescence---particularly the illustrated natural histories and stories of explorers-changed his life. "I am alive today and writing this autobiography," he wrote in1934, "instead of being a worn-out, dismissed and already dead shop assistant, because my leg was broken."

It wasn't a specific injury that started GR as a voracious reader, but as he described it later, his uncertain health as a child played a defining role. He had a number of unexplained ailments: troubling breathing, weak and uncoordinated legs that made walking awkward, and even occasional seizures. So instead of sports and other physical activities, GR was more comfortable exploring through his imagination. He became an avid reader from the age of four.

When GR was born, his father was desperately looking for work. He left Texas, apparently riding the rails to Los Angeles, where his previous job as a railroad cop got him a job on the police force which was expanding in response to the fast-growing city. This job provided a steady but modest income and a home in a working class neighborhood. It was the Great Depression, and GR never forgot his father and mother's generosity towards neighbors and even strangers who weren't as lucky.

When he was old enough, GR took the streetcar to the public library to exchange one bundle of books for another. Back at home he might fortify himself with a stack of crackers held together with peanut butter, and go out on the front porch to sprawl on the old couch in the soft air of a southern California afternoon, and fall "into the dream world of books."

Like HG, GR took to reading with such fervor that his parents were worried he was overdoing it. "I have a terrible hunger for ideas," GR would say years later. " I've had it since my early years. In my youth, I realized I had this terrible hunger for knowledge-like an addict for knowledge. I remember that I just couldn't sit down without my mind working, without reading something, some experience. It seemed that this was more a flaw, this terrible hunger."

But it is common to intelligent children whose imaginations go beyond the boundaries of the expectations of their class. Though their childhoods were separated by 70 years, HG and GR read many of the same kinds of books---of exploration and adventure, both nonfiction and fiction---and read some of the very same books: tales of Robinson Crusoe and Huck Finn, D'Artagnan and Hawkeye, and Gulliver and his travels. This last in particular was to make a strong impression on both of them. And in later years, when they reached a critical point in their writing, they would both turn to the same author they recalled from childhood: Jonathan Swift.

HG and GR were also avid readers of cartoons and comic strips (HG wrote his own illustrated adventures.) But GR had a few sources of stories HG didn't: the movies (including the Flash '>Gordon serials) and the radio adventures of '>The Lone Ranger, '>The Shadow, and '>Buck Rogers of the Twenty-Fifth Century.

GR also had a type of reading that HG didn't: it was called science fiction, and one of its primary authors was H.G. Wells. This is where GR's ill health comes into play again. When GR was 11, there was a boy in his neighborhood who was witty and intelligent, but even more restricted by health problems and disabilities. GR knew what that was like, and befriended the boy, who introduced him to his own special avenue of escape and adventure: a treasure trove of magazines called Amazing, Astounding, and Science Wonder Stories.

These magazines had begun appearing in the late 1920s. It was only in 1929 (just three years before GR discovered them) that editor and writer Hugo Gernsback first used the term "science fiction" to describe the sort of story he was publishing in Amazing Stories.

Gernsback's pulps published new stories but also many of the classics, especially by Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe and H.G. Wells---six of his novels and 17 of his stories appeared in those Science Wonder Stories and Amazing Stories. These pulps not only created the sci-fi industry in America, they introduced Wells to new generations of readers, and writers.

So by the time he was working on ideas for his own science fiction television stories, GR probably absorbed much that came from Wells through other avenues, from other writers, from movies and TV shows that incorporated some Wellsian influence. Of course, GR had read Wells, and not just his scientific romances. Shortly before he completed his first Star Trek outline, Roddenberry had proposed a non-fiction TV series based on HG's The Outline of History.

But it all came very close to not happening. HG's discovery of the universe of stories, and his glimpses of another way of life, at first threatened to destroy him, just as his mother feared.

When GR was born, his father was desperately looking for work. He left Texas, apparently riding the rails to Los Angeles, where his previous job as a railroad cop got him a job on the police force which was expanding in response to the fast-growing city. This job provided a steady but modest income and a home in a working class neighborhood. It was the Great Depression, and GR never forgot his father and mother's generosity towards neighbors and even strangers who weren't as lucky.

When he was old enough, GR took the streetcar to the public library to exchange one bundle of books for another. Back at home he might fortify himself with a stack of crackers held together with peanut butter, and go out on the front porch to sprawl on the old couch in the soft air of a southern California afternoon, and fall "into the dream world of books."

Like HG, GR took to reading with such fervor that his parents were worried he was overdoing it. "I have a terrible hunger for ideas," GR would say years later. " I've had it since my early years. In my youth, I realized I had this terrible hunger for knowledge-like an addict for knowledge. I remember that I just couldn't sit down without my mind working, without reading something, some experience. It seemed that this was more a flaw, this terrible hunger."

But it is common to intelligent children whose imaginations go beyond the boundaries of the expectations of their class. Though their childhoods were separated by 70 years, HG and GR read many of the same kinds of books---of exploration and adventure, both nonfiction and fiction---and read some of the very same books: tales of Robinson Crusoe and Huck Finn, D'Artagnan and Hawkeye, and Gulliver and his travels. This last in particular was to make a strong impression on both of them. And in later years, when they reached a critical point in their writing, they would both turn to the same author they recalled from childhood: Jonathan Swift.

HG and GR were also avid readers of cartoons and comic strips (HG wrote his own illustrated adventures.) But GR had a few sources of stories HG didn't: the movies (including the Flash '>Gordon serials) and the radio adventures of '>The Lone Ranger, '>The Shadow, and '>Buck Rogers of the Twenty-Fifth Century.

GR also had a type of reading that HG didn't: it was called science fiction, and one of its primary authors was H.G. Wells. This is where GR's ill health comes into play again. When GR was 11, there was a boy in his neighborhood who was witty and intelligent, but even more restricted by health problems and disabilities. GR knew what that was like, and befriended the boy, who introduced him to his own special avenue of escape and adventure: a treasure trove of magazines called Amazing, Astounding, and Science Wonder Stories.

These magazines had begun appearing in the late 1920s. It was only in 1929 (just three years before GR discovered them) that editor and writer Hugo Gernsback first used the term "science fiction" to describe the sort of story he was publishing in Amazing Stories.

Gernsback's pulps published new stories but also many of the classics, especially by Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe and H.G. Wells---six of his novels and 17 of his stories appeared in those Science Wonder Stories and Amazing Stories. These pulps not only created the sci-fi industry in America, they introduced Wells to new generations of readers, and writers.

So by the time he was working on ideas for his own science fiction television stories, GR probably absorbed much that came from Wells through other avenues, from other writers, from movies and TV shows that incorporated some Wellsian influence. Of course, GR had read Wells, and not just his scientific romances. Shortly before he completed his first Star Trek outline, Roddenberry had proposed a non-fiction TV series based on HG's The Outline of History.

But it all came very close to not happening. HG's discovery of the universe of stories, and his glimpses of another way of life, at first threatened to destroy him, just as his mother feared.

At the age of 17, Bert Wells was in his second year as an apprentice at a drapier shop. He had failed two previous apprenticeships, and was likely to fail this one. He lived in a dormitory above the shop with other boys similarly apprenticed---their parents had paid substantial sums for them to spend four years learning the trade. He worked thirteen hours a day, six days a week.

On Sundays he was free to stare into the blackness of the sea, determined that if he could not escape this life, he would end it.

Wells was in a provincial town called Southsea. (Ironically, the new doctor in the town was another future writer, Arthur Conan Doyle. Though the owner of the shop where Wells worked was his patient, Doyle and Wells did not meet and become friends until years later.) Wells' work there was petty and wearying, yet he was harried and harassed to move from task to task quickly, efficiently and cheerfully. "The unendurable thing about it was that I was never master of my own attention," he remembered later. The mind-bludgeoning tedium, the chatter and noise, the lack of anything to "touch my imagination and sustain my self-respect," the feelings of being a trapped alien with a foreordained future of more of the same, drove Wells to consider suicide.

To his mother, the apprenticeship was the key to his future. To HG, it was doom. He was a poor apprentice but even if he succeeded, his life would still be precarious.

Wells' son Anthony West outlined what was at stake. "It wasn't just a matter of wanting to have his own way, it was the much graver one of not wanting to be thrown aside and wasted...However liberal that vanished [19th century] order may have been in rewarding the successful, it had no pity on those who fell behind in the struggle to get on. My father was in real danger of being trapped in the worst of all social niches, that of the white-collar worker who had to keep up the appearances of gentility while earning a day-labourer's wage....He knew that he would be as good as finished before he'd begun if he gave way and accepted the role that had been assigned him."

But what was a 17 year old boy going to do to change his future? Wells thought about it all the time, and appealed to his few better-off relatives, with no success. As he thought desperately, he kept remembering his last happy time. Between failed apprenticeships, he had managed a few years of school. Just two years earlier, he'd been a stand-out student at Midhurst Middle School, where he'd begun learning science.

He found the moons of Jupiter through a telescope, and was amazed to stand on land that had once been at the bottom of a Cretaceous sea. He was a debater and ringleader of the imagination---he made up stories that his schoolmates helped him enact. He had a satirical eye in the comics he drew and a sardonic sense of humor in his writing. He was popular and successful. But he had to leave to begin his time at the drapier shop in another town.

So he decided to write to the headmaster at Midhurst and ask for a job. There was new funding from the national government for schools, and he proposed that he be a student teacher. At first the headmaster, who had no doubt about HG's brilliance, didn't think it could be done. Then he relented, but said he couldn't pay much more than room and board. Months later, when he found himself able to make a better offer, Wells was finally able to persuade his parents to let him go. It was the moment that changed his life.

On Sundays he was free to stare into the blackness of the sea, determined that if he could not escape this life, he would end it.

Wells was in a provincial town called Southsea. (Ironically, the new doctor in the town was another future writer, Arthur Conan Doyle. Though the owner of the shop where Wells worked was his patient, Doyle and Wells did not meet and become friends until years later.) Wells' work there was petty and wearying, yet he was harried and harassed to move from task to task quickly, efficiently and cheerfully. "The unendurable thing about it was that I was never master of my own attention," he remembered later. The mind-bludgeoning tedium, the chatter and noise, the lack of anything to "touch my imagination and sustain my self-respect," the feelings of being a trapped alien with a foreordained future of more of the same, drove Wells to consider suicide.

To his mother, the apprenticeship was the key to his future. To HG, it was doom. He was a poor apprentice but even if he succeeded, his life would still be precarious.

Wells' son Anthony West outlined what was at stake. "It wasn't just a matter of wanting to have his own way, it was the much graver one of not wanting to be thrown aside and wasted...However liberal that vanished [19th century] order may have been in rewarding the successful, it had no pity on those who fell behind in the struggle to get on. My father was in real danger of being trapped in the worst of all social niches, that of the white-collar worker who had to keep up the appearances of gentility while earning a day-labourer's wage....He knew that he would be as good as finished before he'd begun if he gave way and accepted the role that had been assigned him."

But what was a 17 year old boy going to do to change his future? Wells thought about it all the time, and appealed to his few better-off relatives, with no success. As he thought desperately, he kept remembering his last happy time. Between failed apprenticeships, he had managed a few years of school. Just two years earlier, he'd been a stand-out student at Midhurst Middle School, where he'd begun learning science.

He found the moons of Jupiter through a telescope, and was amazed to stand on land that had once been at the bottom of a Cretaceous sea. He was a debater and ringleader of the imagination---he made up stories that his schoolmates helped him enact. He had a satirical eye in the comics he drew and a sardonic sense of humor in his writing. He was popular and successful. But he had to leave to begin his time at the drapier shop in another town.

So he decided to write to the headmaster at Midhurst and ask for a job. There was new funding from the national government for schools, and he proposed that he be a student teacher. At first the headmaster, who had no doubt about HG's brilliance, didn't think it could be done. Then he relented, but said he couldn't pay much more than room and board. Months later, when he found himself able to make a better offer, Wells was finally able to persuade his parents to let him go. It was the moment that changed his life.

For soon after he'd found his niche at Midhurst, happily contemplating a career as a teacher and perhaps one day a headmaster, he got a letter in the mail. The results of several national exams he had taken were forwarded to the Normal School of Science, a new university in London organized to train the scientists that growing industry needed. His high marks made him eligible for a scholarship. Wells applied, and was astonished when he got in. He was the first in his family to go to a university.

On the edge of the elegant Kensington Gardens, near the legendary Albert Hall and the great Gothic spire of the Albert Monument, the Normal School of Science campus was a fantasyland of red and yellow brick buildings glistening in the fog: its architecture of turrets and spires, domes and arcades were part Camelot, part Arabian Nights.

For young H.G. Wells, arriving with his "cheap shiny handbag", notebook and colored pencils, it was "one of the great days of my life."

That first year was his most important. For several months he took his first science course from one of the most eminent men in England, T.H. Huxley, a scientist, statesman, education reformer who is remembered most today for being a friend and defender of Charles Darwin.

Learning Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection from Huxley himself would be HG's most important intellectual experience. It would shape and inform his writing for decades, particularly his scientific romances.

HG began making a name as a writer in his student days, when among other articles he published his first attempts at a time travel story in the student magazine he helped to establish. He found himself in London at the height of its power and influence, particularly in science and technology. The city was growing fast, and new newspapers and magazines were springing up. But HG didn't have it easy. His bad health and the effects of this new life took their toll. He tried to make a living as a writer, but was having a hard time.

Then he happened to read a passage in a book by J.M. Barrie (author of "Peter Pan") that suggested to him how he might write for a broader audience. He began getting more assignments, and started publishing a new version of his time travel story in serial installments. But that magazine was sold and his editor fired before the story was finished. Months later, when that editor got a new magazine, he asked Wells to write his time travel story again, and gave him some suggestions on how to make it more popular. The Time Machine was published successfully as a serial, and when it came out in book form, H.G. Wells was launched as an author. He was 29.

On the edge of the elegant Kensington Gardens, near the legendary Albert Hall and the great Gothic spire of the Albert Monument, the Normal School of Science campus was a fantasyland of red and yellow brick buildings glistening in the fog: its architecture of turrets and spires, domes and arcades were part Camelot, part Arabian Nights.

For young H.G. Wells, arriving with his "cheap shiny handbag", notebook and colored pencils, it was "one of the great days of my life."

That first year was his most important. For several months he took his first science course from one of the most eminent men in England, T.H. Huxley, a scientist, statesman, education reformer who is remembered most today for being a friend and defender of Charles Darwin.

Learning Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection from Huxley himself would be HG's most important intellectual experience. It would shape and inform his writing for decades, particularly his scientific romances.

HG began making a name as a writer in his student days, when among other articles he published his first attempts at a time travel story in the student magazine he helped to establish. He found himself in London at the height of its power and influence, particularly in science and technology. The city was growing fast, and new newspapers and magazines were springing up. But HG didn't have it easy. His bad health and the effects of this new life took their toll. He tried to make a living as a writer, but was having a hard time.

Then he happened to read a passage in a book by J.M. Barrie (author of "Peter Pan") that suggested to him how he might write for a broader audience. He began getting more assignments, and started publishing a new version of his time travel story in serial installments. But that magazine was sold and his editor fired before the story was finished. Months later, when that editor got a new magazine, he asked Wells to write his time travel story again, and gave him some suggestions on how to make it more popular. The Time Machine was published successfully as a serial, and when it came out in book form, H.G. Wells was launched as an author. He was 29.

Los Angeles was not the nerve center of the world that London was in the 1890s, but it was a city of the future. And while London had been the center of the most popular storytelling forms of its day, particularly the novel, the Los Angeles of the 1950s was already the undisputed movie capital and was rapidly become the center of the most popular storytelling form of the near future, television.

Though GR was also the first in his family to earn a university degree, and though he took various writing courses over the years, he was not trained as a writer. There were no courses on television writing anyway, since it was still being invented. While working for the Los Angeles Police Department, GR sold stories to "Dragnet," and got scripts of the shows in advance of their airing, so he could read along as he watched. He turned down the sound to study the visual language, and turned his back on the screen to listen to the dialogue and sound effects.

He started selling stories and scripts to other shows but ran into some difficulty until some advice from the successful popular writer, Earle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason) helped him through some rough spots. But this kind of advice was useful in only a limited way. The important quality was imagination, and though GR was thoughtful, philosophical and an avid consumer of information, he also dreamed. "I turn on a kind of mental screening room," GR explained. "I watch whatever is on the screen. I watch their faces, their movements. I see their backgrounds. I listen to their voices."

This is pretty similar to what Wells said about writing his scientific romances. Ideas came to him, he said, as in a dream: he would think of a subject, and images would float before his eyes. "I would discover I was peering into remote and mysterious worlds ruled by an order logical indeed but other than our common sanity."

Then in the early 1960s, when he was becoming increasingly frustrated with what he was and wasn't allowed to write about as television drama, GR remembered someone he'd read in younger days. "I thought with science fiction I might do what Jonathan Swift did when he wrote Gulliver's Travels," Roddenberry told an interviewer. "He lived in a time when you could lose your head for making religious and political comments. I was working in a medium, television, which was heavily censored, and in contemporary shows I found I couldn't talk about sex, politics, religion and the other things I wanted to talk about. It seemed to me that if I had things happen to little polka-dotted people on a far-off planet, I might get past the network censors, as Swift did in his day."

GR is linked to HG by Swift, and the science fiction of consciousness. In a preface to a collection of his early science fiction novels, including The Time Machine, Wells wrote this: "My early, profound and lifelong admiration for Swift, appears again and again in this collection, and it is particularly evident in a predisposition to make the stories reflect upon contemporary political and social discussions."

Though GR was also the first in his family to earn a university degree, and though he took various writing courses over the years, he was not trained as a writer. There were no courses on television writing anyway, since it was still being invented. While working for the Los Angeles Police Department, GR sold stories to "Dragnet," and got scripts of the shows in advance of their airing, so he could read along as he watched. He turned down the sound to study the visual language, and turned his back on the screen to listen to the dialogue and sound effects.

He started selling stories and scripts to other shows but ran into some difficulty until some advice from the successful popular writer, Earle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason) helped him through some rough spots. But this kind of advice was useful in only a limited way. The important quality was imagination, and though GR was thoughtful, philosophical and an avid consumer of information, he also dreamed. "I turn on a kind of mental screening room," GR explained. "I watch whatever is on the screen. I watch their faces, their movements. I see their backgrounds. I listen to their voices."

This is pretty similar to what Wells said about writing his scientific romances. Ideas came to him, he said, as in a dream: he would think of a subject, and images would float before his eyes. "I would discover I was peering into remote and mysterious worlds ruled by an order logical indeed but other than our common sanity."

Then in the early 1960s, when he was becoming increasingly frustrated with what he was and wasn't allowed to write about as television drama, GR remembered someone he'd read in younger days. "I thought with science fiction I might do what Jonathan Swift did when he wrote Gulliver's Travels," Roddenberry told an interviewer. "He lived in a time when you could lose your head for making religious and political comments. I was working in a medium, television, which was heavily censored, and in contemporary shows I found I couldn't talk about sex, politics, religion and the other things I wanted to talk about. It seemed to me that if I had things happen to little polka-dotted people on a far-off planet, I might get past the network censors, as Swift did in his day."

GR is linked to HG by Swift, and the science fiction of consciousness. In a preface to a collection of his early science fiction novels, including The Time Machine, Wells wrote this: "My early, profound and lifelong admiration for Swift, appears again and again in this collection, and it is particularly evident in a predisposition to make the stories reflect upon contemporary political and social discussions."

When GR began putting together the Star Trek universe, he and the other principal participants followed rules that were new to television science fiction. But many of these rules for effective science fiction had become basic to the best sci-fi authors, and nearly all of them originated with H.G. Wells.

HG described them in the preface to the aforementioned collection of tales he had written mostly in the 1890s, in what could have been a prescription for Star Trek in 1965.

The first ingredient, Wells wrote, is the element of the fantastic: "the magic trick." The writer's job is to build the reader's belief. For science fiction, there must be some scientific basis or at least plausibility. If all else fails, "an ingenious use of scientific patter might with advantage be substituted." (We call it technobabble.)

To bolster believability, Wells said, there should be only one fantastic element, one basic "what if." Its credibility depends partly on surrounding the unexpected with lots of the expected. The writer must help the reader "in every possible unobtrusive way to domesticate" the fantastic element. The reader has to be drawn into the story-and too many things that go against known reality or common sense would likely destroy that suspension of disbelief. "Nothing remains interesting when anything may happen."

"The thing that makes such imaginations interesting is their translation into commonplace terms, and a rigid exclusion of other marvels from the story. Then it becomes human," Wells wrote. " 'How would you feel and what might not happen to you?' is the typical question... "

"As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real," Wells concluded. "[T]he whole interest becomes the interest of looking a human feelings and human ways, from the new angle that has been acquired."

HG also comments on the role of his fictions in anticipating the future. Although for awhile in the early 20th century, he advocated a scientific study of future trends (and became the first modern futurist), Wells denies that is the intent of his fiction. "...these stories of mine collected here do not pretend to deal with possible things," he wrote. "...they are exercises of the imagination in a quite different field..." His intent often was "a broad criticism of human institutions and limitations, as in Gulliver's Travels."

But in creating plausible futures, Wells, like Star Trek, anticipated actual inventions and happenings. HG's most spectacular hit was imagining (and naming) the atomic bomb, decades in advance.

One more similarity is worth mentioning. GR is often criticized for taking too much credit for Star Trek and the ideas presented in it. Perhaps he did. But few ideas are original, and it is the synthesis and presentation of ideas that is important in storytelling. The same was true of HG.

"Wells was a brilliant man, but he was not an original thinker," writes Frank McConnell. "His gift was for imagining, for realizing firmly, almost visually, the implications of his age's philosophy and science, and for communicating those implications to his readers with the urgency of myth. The same may be said of Shakespeare."

The same may be said of GR, foremost among those individuals who, working together, created Star Treks.

HG described them in the preface to the aforementioned collection of tales he had written mostly in the 1890s, in what could have been a prescription for Star Trek in 1965.

The first ingredient, Wells wrote, is the element of the fantastic: "the magic trick." The writer's job is to build the reader's belief. For science fiction, there must be some scientific basis or at least plausibility. If all else fails, "an ingenious use of scientific patter might with advantage be substituted." (We call it technobabble.)

To bolster believability, Wells said, there should be only one fantastic element, one basic "what if." Its credibility depends partly on surrounding the unexpected with lots of the expected. The writer must help the reader "in every possible unobtrusive way to domesticate" the fantastic element. The reader has to be drawn into the story-and too many things that go against known reality or common sense would likely destroy that suspension of disbelief. "Nothing remains interesting when anything may happen."

"The thing that makes such imaginations interesting is their translation into commonplace terms, and a rigid exclusion of other marvels from the story. Then it becomes human," Wells wrote. " 'How would you feel and what might not happen to you?' is the typical question... "

"As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real," Wells concluded. "[T]he whole interest becomes the interest of looking a human feelings and human ways, from the new angle that has been acquired."

HG also comments on the role of his fictions in anticipating the future. Although for awhile in the early 20th century, he advocated a scientific study of future trends (and became the first modern futurist), Wells denies that is the intent of his fiction. "...these stories of mine collected here do not pretend to deal with possible things," he wrote. "...they are exercises of the imagination in a quite different field..." His intent often was "a broad criticism of human institutions and limitations, as in Gulliver's Travels."

But in creating plausible futures, Wells, like Star Trek, anticipated actual inventions and happenings. HG's most spectacular hit was imagining (and naming) the atomic bomb, decades in advance.

One more similarity is worth mentioning. GR is often criticized for taking too much credit for Star Trek and the ideas presented in it. Perhaps he did. But few ideas are original, and it is the synthesis and presentation of ideas that is important in storytelling. The same was true of HG.

"Wells was a brilliant man, but he was not an original thinker," writes Frank McConnell. "His gift was for imagining, for realizing firmly, almost visually, the implications of his age's philosophy and science, and for communicating those implications to his readers with the urgency of myth. The same may be said of Shakespeare."

The same may be said of GR, foremost among those individuals who, working together, created Star Treks.

There is one final connection to make between HG and GR, and it is another writer. Although HG essentially created science fiction as we know it in the 1890s, it more or less languished until the pulps inspired its reemergence in America in the 1930s. But Wells had one prominent younger disciple: Olaf Stapledon. Not well known even by science fiction fans, he is highly praised by science fiction writers and critics, and a writer Roddenberry read and studied throughout his years working on Star Trek.

In novels like '>Last and First Men and Star Maker, Stapledon combined Darwin and Einstein in the first evolutionary histories and stories of galactic civilizations that became a staple of science fiction of all kinds. His visions were also highly spiritual and profoundly influenced by war, in ways that GR could appreciate. Like both HG and GR, Stapledon believed that humanity was still in an early stage of childhood or adolescence.

"His was the noblest and most civilized mind I have ever encountered," Arthur C. Clarke said of Stapledon. "His prose is as lucid as his imagination is huge and frightening," Brian Aldiss wrote. "Star Maker is really the one great grey holy book of science fiction." When Allan Asherman interviewed Gene Roddenberry as he was beginning production on Star Trek: The Next Generation, Roddenberry was re-reading Stapledon. Sam Peeples remembered lending a couple of Stapledon's hard-to-find novels to GR when he was conceiving Star Trek in the 1960s. Of Roddenberry's original concept for Star Trek, Sam Peeples told Asherman, "I think he] wanted to do a more realistic, a more earthy version of Olaf Stapledon's concepts that were so enormous and staggering."

In novels like '>Last and First Men and Star Maker, Stapledon combined Darwin and Einstein in the first evolutionary histories and stories of galactic civilizations that became a staple of science fiction of all kinds. His visions were also highly spiritual and profoundly influenced by war, in ways that GR could appreciate. Like both HG and GR, Stapledon believed that humanity was still in an early stage of childhood or adolescence.

"His was the noblest and most civilized mind I have ever encountered," Arthur C. Clarke said of Stapledon. "His prose is as lucid as his imagination is huge and frightening," Brian Aldiss wrote. "Star Maker is really the one great grey holy book of science fiction." When Allan Asherman interviewed Gene Roddenberry as he was beginning production on Star Trek: The Next Generation, Roddenberry was re-reading Stapledon. Sam Peeples remembered lending a couple of Stapledon's hard-to-find novels to GR when he was conceiving Star Trek in the 1960s. Of Roddenberry's original concept for Star Trek, Sam Peeples told Asherman, "I think he] wanted to do a more realistic, a more earthy version of Olaf Stapledon's concepts that were so enormous and staggering."

Labels:

Gene Roddenberry,

HG Wells,

Olaf Stapledon,

Trek history

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)