Kirk and Spock visit the Cetacean Institute and join a tour. A question from a teenager on the tour is the only "Moby Dick" reference in this movie, though that novel was thematically important to the first film of this trilogy, and would be again later in the Star Trek series. But as characters in this story, the whales are real, their natural behavior being the point (though perhaps stretched a bit in extraterrestrial communication.) No, the teenager is told, whales don't attack and eat people. It is rather the other way around.

The tour sees a film of proud whalers slaughtering whales (the look on the faces of the elderly ladies in the front row of the tour says everything that needs to be said about this) and when they move to a window with an underwater view of the two whales, Kirk is aghast to see that Spock is in the water, attempting a mind-meld with one of the whales in full view of the tour. His semi-mugging facial expressions, and particularly his hand on his face in frozen takes, always remind me of George C. Scott as General Buck Turgidson in

Dr. Strangelove.

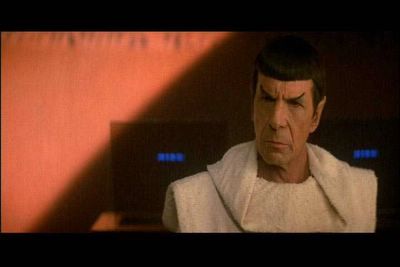

Spock continues his deadpan cluelessness, complete with misapplied colorful metaphors, but has done something crucial---he's communicated with the whales, and they with him. He acknowledges that the whales are not their property and can't ethically be taken against their will, but has explained their mission and the whales have consented to go with them. The whales have also "told" him that they are unhappy with how humans have treated them, a sadly funny line because it is so obvious, and so desperately sad that we know we would react differently if we actually heard whales say this, when we should be able to figure it out for ourselves.

When the tour group hears the names of the whales---George and Gracie---they laugh, so presumably in the late 1980s they still know this classic comedy pairing of George Burns and Gracie Allen, who were among TV's first stars in the 1950s. (Coincidentally or not, Leonard Nimoy has said that for the Spock-McCoy verbal confrontations in the series, he patterned his performance after George Burns responding to Gracie Allen.)

This second mention of George and Gracie ushers in a series of comedy pairings: Kirk and Spock do an Abbott and Costello-type "Who's on first?" routine to the tune of "Do You Guys Like Italian?" (No, yes, yes, no, no, yes, no, yes, I love Italian, and so do you. Yes.)

Scotty and McCoy do a Laurel and Hardy turn, with the help of a straight man and a quaint computer that lacks voice recognition. Off to collect some fresh photons from the nuclear wessel they found ("And kepten, it is the Enterprise"), Uhura and Chekov do a kind of Martin and Lewis, with Uhura the romantic straight man (and singer), and Walter Koenig getting to do physical comedy, as well as some verbal miscommunication with a no-nonsense naval officer. This is his best scene in the movies and he makes the most of it. (He caps it with his post-operative answer to Kirk's name and rank request, with a seraphic "Admiral.")

There is even a romantic comedy pairing, a Tracy and Hepburn moment between Kirk and the young cetacean biologist, Gillian Taylor, played by Catherine Hicks.

Guest actors in Trek movies have had two basic functions: either they are the bad guys, or more rarely, they are like Gillian: characters that start out skeptically and end up collaborating with our heroes, all the while providing a sympathetic outsider point of view. The most conspicuous other example would be Alfre Woodard's character in

First Contact, named Lily. Gillian and Lily are also the designated representatives of the audience, especially that portion not comprised of Star Trek fans. She is their point of reference, the person they can identify with: Alice in Wonderland. It probably isn't too much of a coincidence that Star Trek IV and First Contact were the two most popular Trek features.

Catherine Hicks played Bill Murray's initial love interest who becomes something of a villain in the vastly underrated "

Razor's Edge" a few years before this movie. A few years later she was doing steamy love scenes in "

Laguna Heat" and she had portrayed Marilyn Monroe in a TV biography. In this film, though she's given fairly clunky dialogue, Gillian is intelligent, professional, a little awkward, conflicted and vulnerable; she's pretty, with a healthy glow and energy, and a sense of humor and fun.

Her emotional idealism (she embodies biophilia) and only partially successful urban cynicism give her character enough colors to keep Kirk a little off balance, which keeps Shatner on his game. Their scene in the pizza restaurant is important to moving the story, but it's also a romantic comedy scene: her probing skepticism, flirtatious curiosity and hope, with flashes of her growing despair over the fate of the whales, run up against Shatner's Kirk, playing a charming game of poker, while also charming the lady. Meanwhile Shatner is layering quiet, believable bits of business---like reacting to the taste of beer---and sometimes taking the quieter reactive role in their bantering: "No, I'm from Iowa," he says patiently, adding softly, "I only work in outer space."

Shatner worked with Spencer Tracy once (and insulted him by trying to compliment him as a movie actor who was just as good as theatre actors) in a drama ("

Judgment at Nuremberg.") But his performance in this scene is more like Tracy in those classic comedies, where he has to deal with the mercurial out-there energies of Katherine Hepburn.

All the comedy adds to the high-spirited adventure, but it all contributes to the step-by-step story: attempts to solve a problem, the solution, which leads to a new problem, etc. Kirk and Spock have located the whales, but they also learn that George and Gracie are going to be released and put into jeopardy from whalers---they just don't know when. Scotty and McCoy have found a manufacturer capable of making the transparent aluminum they need for the whale tank in the Bird of Prey; after they've transformed a stunned plant supervisor into a genius inventor (adding more smoke and mirrors to obscure time travel paradoxes, and of course weathering more communications problems), they have to get it transported. That's Sulu's job, so he commandeers a Huey helicopter, which he has to figure out how to fly (his comic solo). (Meanwhile Special Effects had to figure out how to portray it, and wound up filming a remote control toy helicopter from Japan against the San Francisco skyline on Alcatraz Island, a solution that would have worked fifty years before.)

Uhura and Chekov succeed in capturing the nuclear particles needed to restart the Klingon warp drive from the aircraft carrier nuclear engines, but Chekov is captured and seriously injured in his attempt to escape.

Meanwhile, Gillian has learned the whales were secretly sent to Alaska and released, and decides to let go of her skepticism and alert Kirk. She literally runs into the cloaked Bird of Prey in Golden Gate Park (which is actually Will Rogers Park in Los Angeles, where Rogers, famous as a lariat-twirling man of the people, played polo.) After she feels around the invisible ship, standard mime training paying off for once, Kirk beams her aboard, her first transporter experience. Nimoy shows her rematerializing in a long shot, with her girlish figure framed by the transporter pad walls as if she were about to step out of a book. Which she is, as Kirk notes: "Hello, Alice. Welcome to Wonderland." Now Alice is in the adventure.