Comrades

When I think of camaraderie I've experienced in my life, two examples come to mind first, one of which is directly related to Star Trek. I've told this story before, so here's the short version. While Star Trek was becoming really popular in syndication, I was writing and editing for a weekly alternative newspaper in Washington, D.C. I don't know who started calling me "Spock" at the newspaper office, but I was second in command at the time (the Arts section editor), and I did keep a reasonable, rational demeanor in what was a frenetic and emotionally charged scene.

But it was a great group and we had a great time together. We were all in our twenties, we worked hard and played hard and usually did both together. I remember a party many of us attended, and wound up on one side of the room, talking to each other. The Spock thing reached its apex one day when I was walking across the editorial office---which was one big room in an old 3 story frame house in Adams-Morgan that doubtless was later gentrified into the real estate stratosphere, but then was a cheap rent among derelict buildings. As I walked I saw ahead of me two guys, both fellow editorial staffers, standing toe to toe and shouting at each other. Their argument was attracting notice as I got closer to them, and it was getting louder. But just as I was about to pass them, I gave them each a Vulcan neck pinch. Immediately, without a word, they both sank to the floor.

That's how powerful Star Trek was in our world, and that's what our camaraderie was like. Soon I became editor of the whole paper, so I also became Captain Kirk. And I began to act like him at times---I actually threatened to expose a congressional secret when a source got cold feet and wanted to withdraw a story we already had at the printer. It would have ruined us. I had to save my ship! The source backed down, there was no real reason for his second thoughts, no harm would be done, as I knew. One of my staff then asked me if I had been bluffing. I just gave my best enigmatic Kirk-like grin.

But my second memory of camaraderie is maybe more pertinent to the subject at hand. It was my relationship with two friends, one of whom I'd known since grade school, the other since we began high school. In high school we started hanging out together and formed a comedy and music group one summer. At first I wrote skits we did on tape, mostly topical satires in the early 60s style of Stan Freeberg and "That Was the Week That Was," using my father's discarded reel-to-reel. Then we branched out to live performances for church groups in the summer. Finally we became a musical group, first with folk music, and then something like folk-rock. We spent a lot of time together, working out songs, teaching each other guitar parts, experimenting with singing parts. The three of us wrote songs, too, sometimes in different collaborations of two, sometimes alone. But then the songs were never really finished until the three of us had worked on them. (We knew this was how the Beatles worked.)

Looking back (and actually I think I knew this at the time), we got to know each other in ways that most people don't, who don't work together on creative endeavors. Simply because we did this weird thing of making music together, and this was so important to us, we were different. We would communicate with each other through the songs we wrote or chose, and how we sang and played them. We were creating and developing both as individuals, and as a group. We had to trust and support each other. At the same time, that also meant that we had to trust and support who we were as individuals. We had our differences (and rivalries over girls) and our bad patches. But our friendship has endured---Mike and Clayton remain my closest friends, the ones I know I can always depend on. And the camaraderie has endured as well. We've gone our separate ways, we live very different lives, and right now there are thousands of miles between us. But whenever we get together, it's as if time and space never existed.

Maybe it was this experience that has made theatre so attractive to me. I'm basically an introvert and extraverted actors tend to exhaust me. Yet they are also so enlivening, so expressive, I love being with them, and I love working with them---as long as I can eventually go home. I work mostly in solitude as a writer, but I love the idea of collaboration and wish I'd had more opportunity to do it on imaginative, creative projects. Not just collaborative writing, but working with actors and directors. This is perhaps a long way, and certain a personal way, of getting to this point: camaraderie is very attractive in itself, and it is strongest and most special when it emanates from creative collaboration.

The model for camaraderie, this combination of fierce loyalty with high spirited play, is usually among soldiers, or sailors. They spend all their time together in close quarters, usually under bad conditions, and often in grave danger. They share boredom, they share tension, they depend on each other for information, for counsel, for entertainment, sometimes for their daily bread, and in the most fraught situations, for their very lives.

This is the side of camaraderie we have seen in Star Trek: depending on each other, risking and willingly sacrificing one's life for one's comrades. In a way it is the essence of human society, which is what the King in the third Lord of the Rings movie essentially tells his troops before their final desperate attack---that someday men will cease to be men and not fight for their comrades, but not today. In a way, this is also the horrible tragedy of war, when old men with all the power sit safe at home while they send young men to fight and die for each other in some distant land, in some usually unnecessary war. For in the end this is what men at war fight and die for---even after king and country and the girl back home have begun to fade: they fight and kill and die for each other. This is their last certainty.

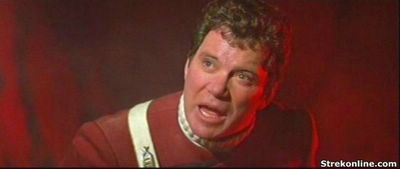

In Star Trek V we see that kind of camaraderie still present, but less solemnly so. As Shatner says somewhere in the commentary, there's always been an energy and an urgency in the acting in Star Trek, and the subjects are essentially serious. By this time, though, they were free to express that other side of camaraderie, the affection and the fun.

And by this time, the cast was clearly up to it. From the small moments of the supporting cast regular crew to the rich byplay among the trinity, the humor in Star Trek V is freer and more skillfully accomplished than ever before. And it was made possible by the basic seriousness of the saga. The series established this credibility and trust, both among the characters and by the audience in the characters. These characters earned that trust over time, so these new elements were like flowers blooming in wild new colors. They knew their characters so well that they could express these new colors, with wonderful ease.

Shatner especially had redefined Kirk. His human humor and his aging seemed to go together naturally as the character's growth. The humor and its timing that was still a bit awkward at times in Star Trek II had found the right rhythm in IV and it never faltered in V, and hardly ever afterwards. As a director as well as actor, Shatner turned this humor of camaraderie into the pacing of group scenes. These are a joy to watch now. They're classic.